Leaving writing and Quake mapping

When I was 19 or 20 and reading a lot of books, I started to feel a longing to be a fiction writer that I wouldn’t really feel brave enough to satisfy for years. I have a lot of sympathy for my self back then. How he would write in his diary and treat all his assignments very seriously, but feel extreme embarrassment to think of himself as a writer. Even still he kept writing and eventually it was no longer embarrassing. Writing seemed like something everyone could do, something everyone was doing, but he just happened to care about it in a certain way that others seemed to not. Stories seemed to be important to him, so, naturally, he became a writer of fiction.

Then years pass and he obtains perspective. He sees the thing more completely than he ever has before. Writing is a neurotic indulgence, which isn’t necessarily bad. But drafting all the time is unhealthy. Authorship is tedious and authors are boring. He is long tired of celebrating publication accomplishments before he will allow himself to accept how he feels. He knows nobody is reading anybody’s writing but everyone is getting published. It’s pathetic.

Now I am 27 and I have completely lost the anxiety about losing the writing knack. I know now I will always be a writer.

So, why keep writing?

Because writing involves me (a strange phrase).

It’s in the movement of my thought, how I explain my self to myself, for now a crucial part in the way I touch people. There is no walking away from the world I know.

But to be less metaphorical, I keep writing because I can’t give up the tweet or forum post, my diary, and I still think that writing has something to show me about doing scholarship.

Also, stories are still important to me. When I think about it, maybe I care more about storytelling than writing. I might just call them the same thing. I don’t want to write fiction, but I still want to find ways to write stories. And one way I know of is writing stories by designing space. So I am learning how to make maps in the 1996 videogame Quake.

I started doing this over the long Fall break after I wrapped up finals. It was a response to noticing a bad behavioral pattern, where I would commit all my free time to writing, either finishing or revising stories, or doing something more academic. The story that broke me was called “Nouveau Roman Suburbs”. It may have even been a good one, I know I really like that name. Fall quarter was full of such extreme emotional highs and lows, it left me pretty beat, so I don’t think there was enough energy left in my fragile vessel to throw up the usual defenses and protect my self from this realization: I wasn’t having any fun and so could no longer see the point in keeping on like this.

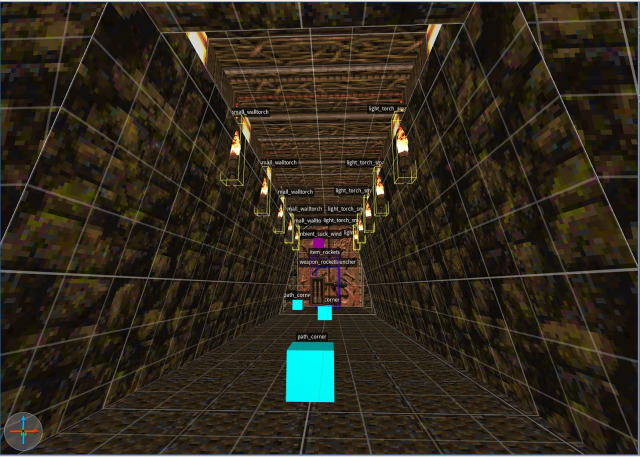

So, I pulled up a YouTube playlist made by a veteran Quake mapper named dumptruck_ds and learned what programs to use and how to set up my files in the right way, and how to take all this and start drawing little lego blocks (called brushes in the game engine) to build maps and start writing stories in a new way.

Drawing a brush. This is how you make maps, one brush at a time.

The tutorial videos sort of hopped around between different files to demonstrate this or that aspect of making maps, giving them a clear presentation that was easy to follow, each tutorial took place in a basically blank map where the thing being demonstrated was the only thing to really look at.

I didn’t follow this exactly, however.

Each new thing introduced I just kept adding onto the very first room I ever drew, until, after a few days had passed, I was playing in this really cramped space with a really novel and appealing incoherence to it. This was the first map I finished. I called it “Crowded Mouth”, like a mouth with too many teeth in it.

The above video is a complete playthrough of the map in its final state. Shooting enemies and pressing buttons and finding keys is quintessential Quake. This is the real thing.

Pictures below show Crowded Mouth’s progression from a small thing to the final, more elaborate and cramped thing it became. I also try to account what it felt like to put it all together. Where it felt familiar and where it felt different.

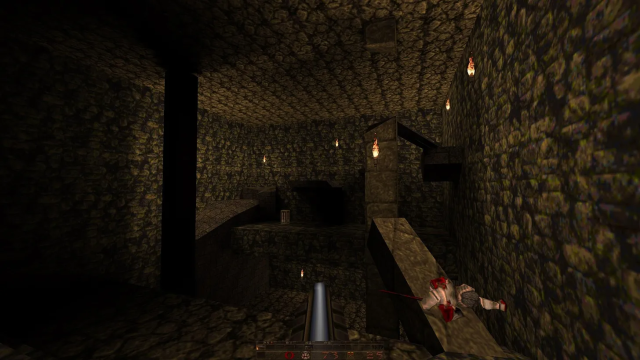

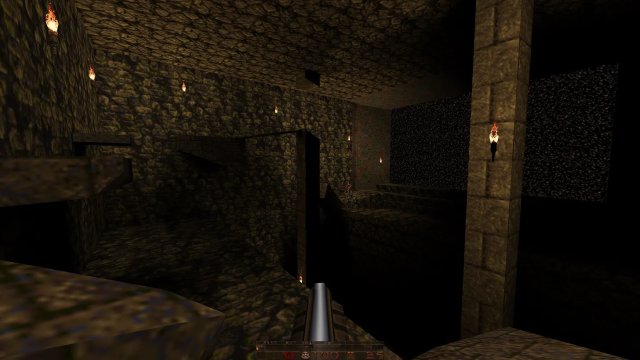

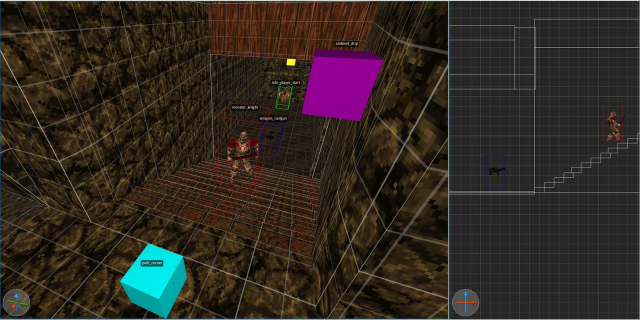

(Above) A wide view of the room with a pit that I designed during my very first session. Later I would expand it by adding a hallway that lead to a door (below, an in-game perspective and then the view from the program). The bad looking archway above the door was then the hardest piece of geometry I ever drew. By now I’ve drawn weirder shapes.

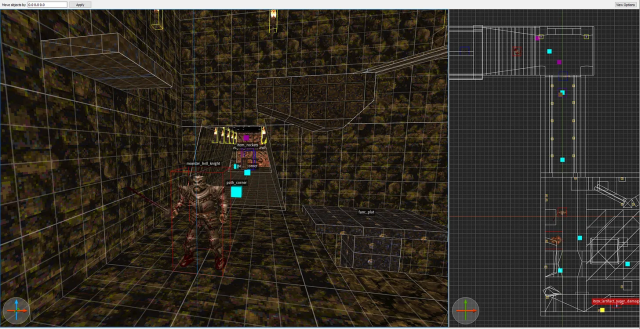

(Sequence Below) More additions off that door hallway, including stairs, an enemy with special coded behavior to walk up the stairs and move around the corner; that enemy would meet up with an even tougher enemy, and if the player alerted any one of them they would turn around and come after them;

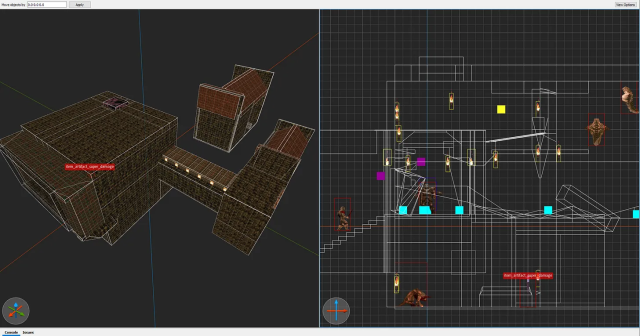

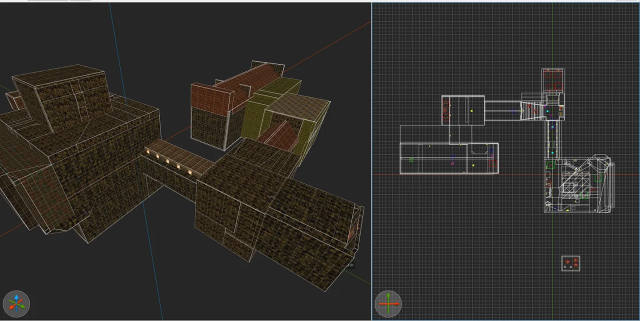

(Below) a bird’s-eye view of the whole exterior of the level, which no player would ever see. You can tell how it’s just slabs of things making walls and floors and roofs. The view next to it is a schematic view of the level in 2D.

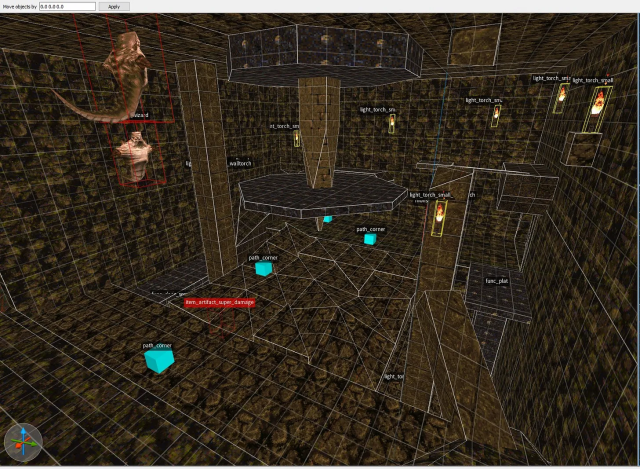

After expanding the level I went back and complicated the initial room I created (the one with the pit shown above) so that it would be more fun and lively to play and move in. This was the start of what I think is the “embellishing work” of map making, the act of iterating on a rougher idea and refining it, prototyping, which feels a lot like writing.

(Below) another bird’s-eye view but at the very end of the map’s development. You can watch the video above and trace the progression through the map if you notice that the start of the map is the furthest building in the picture below and its end is in the big one on the left.

I was really pleased to discover map making to be a lot of fun for me. It pulls me in the same way that writing does. Focus hones in on one element, of a sentence, of the geometry of a broken pillar I intend the player to jump onto, and I am affecting the whole by touching just one part in one very minute way. And when the whole is complete, when the story can be read from start to finish or the map played from beginning to end, there still remains little tweaks and regrets that argue the process is never really done.

This is just like writing. In “Game Design as Narrative Architecture” Henry Jenkins argues that making maps can even be considered storytelling:

“Spacial stories are not badly constructed stories; rather they are stories which respond to alternative aesthetic principles, privileging spatial exploration over plot development. Spatial stories are held together by broadly defined goals and conflicts and pushed forward by the character’s movement across the map…. Read in this light, a story is less a temporal structure than a body of information.”

Applications for rhetorical and pedagogical theory abound in constructing architectures that tell a particular story. And this is a genre I have always been better at reading than any other. Growing up playing first-person 3D videogames, I always got a lot out of exploring spaces and learning their stories from how they look. Inhabiting an observational genre like this for so long, it’s no wonder that most of my prose stories involve spectators or passive protagonists being moved here or there. But that was always frustrating and very hard to get people to care about in the world of short story publication.

I hope that jumping into map making leads me to develop a strength in telling stories of this kind. Maybe later I can return to prose stories, having figured out he observational story in a different medium, and try my hand at a mystery or family drama!

The road ahead of me is untextured, polygonal, floating over lava in a pure voidspace. This is also a picture of my next map project, Human City. More about that next time.